Learning How to Learn When You are Learning

“How do you know when you are learning?”

This is a question important to answer, especially in its more nuanced form: “When you are learning, how does your sense of how well you are learning match the answer an expert watching you might give?” It turns out that people often get it wrong, which leads to any number of bad decisions in their day-to-day pursuit of an education.

A group at Harvard led by Louis Deslauriers, Logan S. McCarty, and others recently did an in-depth comparison of students’ self-reported perception of learning (how well they thought they were learning) with their actual learning (how well they demonstrated their learning). This was done in an introductory college physics course that was taught in one of two ways: either by active instruction (following best practices in the discipline), or passive instruction (with lectures by experienced and highly rated instructors). Both groups received identical class content and hand-outs, students were randomly assigned, and the instructor made no effort to persuade students of the benefit of either method. The researchers found that:

Students in active classrooms learned more… but their perception of learning, while positive, was lower than that of their peers in passive environments.

These results suggest that when students experience the increased cognitive effort associated with active learning, they initially take that effort to signify poorer learning. That disconnect may have a detrimental effect on students’ motivation, engagement, and ability to self-regulate their own learning. Although students can, on their own, discover the increased value of being actively engaged during a semester-long course, their learning may be impaired during the initial part of the course.

This is a remarkable finding and one that is directly relevant to the work that we are doing with Quest Forward Learning.

One way of understanding these results is to recognize that feelings of ignorance, frustration, and challenge are natural elements of the learning process and do not signify either failing to learn or inability to understand the subject at hand. If one sees learning as a transformative growth process, then it would be surprising if students did not have such feelings while learning.

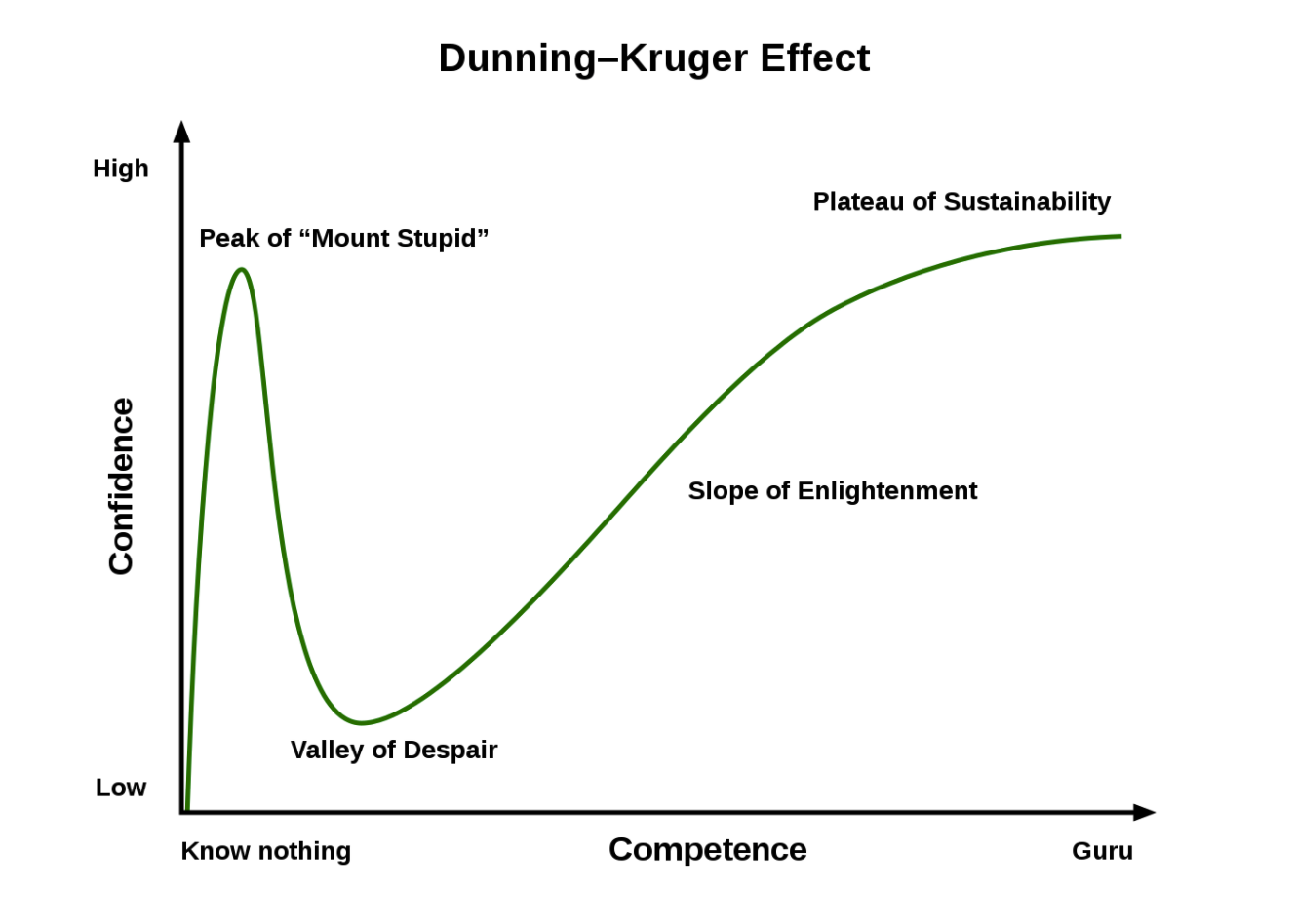

Another way to think of this is in terms of the rate at which students while learning progress along the knowledge curve that defines the “Dunning-Kruger Effect.”

Students in a passive lecture classroom can spend more time climbing the peak of “Mount Stupid” because they are not being asked to put their knowledge to work on a daily basis. Students in an active classroom more readily progress into the Valley of Despair because they have to engage actively with what they are learning and as such discover that there remains much that they do not know, on a daily basis. That the passive learners are in the subjective ascent while the active learners are in the subjective descent shows how it might be that the person actively learning could think that they are learning less than their passive compatriots.

How are we to understand this difference between learning and the perception of learning in the context of Quest Forward Learning?

We often say that Quest Forward Academy students learn how to learn. Equally important, in this process of learning how to learn, is for students to learn how to tell when they are learning.

Learning to tell when you are learning is analogous to learning to know when you don’t know something. Awareness of one’s own ignorance should properly be seen as an invitation to learn. But how should one go about learning?

One needs to do more than simply engage in “learning activities.” Sitting in a classroom and listening to lectures may feel like a learning activity, in the same way that going to school may feel like a learning activity. But really these are only markers for the potential of learning to occur, similar to the way that buying a book is a marker of the potential for reading to occur. One may feel closer to knowledge after buying a book, but until one actually starts engaging with the content of the book one is not actually learning anything from it.

Attending to the process of learning is the key. Learning is not zero-one; it is not sufficient to say “I am engaging with this material. I am sitting in a classroom hearing lectures on it.” For any process of learning to be effective, feedback is essential. It is only through feedback that one can know that one is making progress and that one can know when to change course. Without feedback, one cannot know whether one is actually learning; one can only know that one is engaged in a process the outcome of which could be learning.

Feedback alone is not optimal, however, unless it comes from someone who knows what it is like to traverse the knowledge curve, and who understands where you are in your personal journey. This is why Quest Forward Learning stresses the importance of mentors, who can understand this, over lecturers who merely dispense information. A mentor is able to answer the questions of “how can I learn this?” and “how do I know that I am learning it?”

This is also part of the motivation behind the focus on skills in Quest Forward Learning. Skills, and the demonstration of skills, are the process through which learning occurs, and it is the place where mentors can have the greatest impact on learning. Equally important is the role of self-reflection on how well one is mastering skills or demonstrating learning. Only by turning the critical lens inward can students develop the awareness of what they need to be doing in order to best develop the knowledge and skills that they are seeking.

How then can students learn how when they are learning?

To all students I put as the answer to that question thusly: if you are not learning how to learn and are not learning to tell when you are learning, then the one conclusion you should draw is that it is time to find another school. Just as not knowing is an invitation to learn, not knowing that you are learning is an invitation to change how you are learning.