Resource Spotlight – Journey to Effective Feedback

Nearly half of all teachers leave the profession within the first five years.

This statistic isn’t just scary for principals looking to fill positions. Evidence shows that the benefit to students increases dramatically when teachers have three or more years of classroom experience. Becoming an excellent, veteran educator is not a short, linear path; it’s a process of observation, experimentation, reflection, and growth. And the elusive notion of effective feedback, not just assessment, (and definitely not just grading) is a work process that can’t be perfected in the first six months. I say this from experience.

When I started teaching, I joked that I was joining the family business. I had the benefit of knowledge passed down through a family of teachers, but I didn’t have an ed background to go with my undergraduate English degree. In those early days, I had a (paper!) lesson plan book with little squares, into which I wrote things like “start The Odyssey” and “vocabulary quiz 5,” but not much else in terms of planning or pedagogy.

I learned a lot about teaching teenagers during those first few years, but it wasn’t until I went to the George Washington University and got my M.Ed. that I really came out swinging with a more thoughtful approach to planning. I had learned critically important concepts:

- I should be helping my students construct knowledge not regurgitate it;

- I needed to design my units backwards from an assessment that was both authentic and relevant; and

- I couldn’t do any teaching until I built a classroom climate that allowed students to take risks and trust the process of doing hard things.

My journey as an educator didn’t stop after grad school. I started at a new school and found a next door teacher bestie who inspired me on a daily basis. I learned to collaborate and create with colleagues, learned the importance of looking for the best even in the most difficult of students, and learned to close the door and teach with confidence, even if my admin wanted me to teach non-fiction texts about HVAC systems instead of poetry.

But there came a day when I saw a student toss a graded essay in the recycling bin, just moments after I handed it to him. After hours of grading and thoughtful comments, this student had no use for my feedback. It didn’t help him move forward, because he had already moved on. I had planned engaging, active, student-centered activities and assessments. But I had completely neglected a crucial element: effective feedback.

Beyond writing conferences to scaffold the essay process, my students didn’t have the chance to apply the feedback I was giving them. I had no idea how to bring my students in as partners in the feedback cycle, rather than just recipients of task-oriented suggestions. My feedback was a final judgment, not a step in the learning process or a way to grow. I needed to shift my approach and plan for feedback, with the same intentionality that I planned Socratic seminars for The Stranger and interactive “murder boards” for Chronicle of a Death Foretold.

I learned how to make feedback and the feedback cycle a part of every class, not an afterthought while I entered grades. For this to happen, I had to make unit and lesson plans that used backwards design and the feedback cycle as foundational structures. I had to consider how I could support students through every step of the feedback cycle.

If I could go back in time to give myself advice during those first couple of years of teaching, I’d have a lot to say. But my advice about feedback and learning could be summed up in three basic reminders:

-

- Create intentional feedback opportunities throughout the lesson plan. Ideally, this should happen right from the beginning of the planning process. And make it a priority to embed opportunities that give students ownership of their learning strategies, such as co-creating success criteria, pairing self-assessment activities with student-friendly rubrics, or even just quick checks like Marzano’s four finger scale.

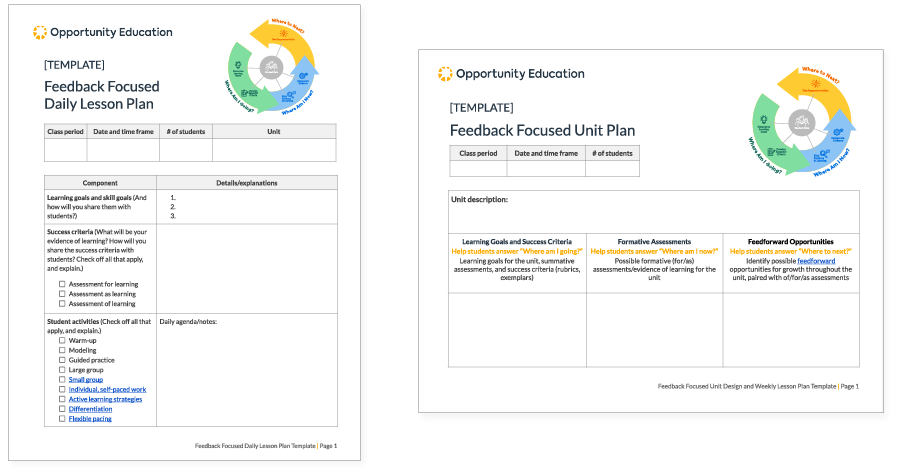

- Take advantage of available resources. No teacher has time to create everything on their own. Using a template or taking elements from a template like this Feedback Focused Daily Lesson Plan or Feedback Focused Unit Plan can help get you started.

- Recognize reality and make plans that you can follow through on. Feedback can take different forms. It’s not always possible to provide in-depth, one-to-one feedback for every student in every class. I’ve posted exemplars built from past student work and done mini-lessons on problem areas as a form of group feedback when it makes sense. And sometimes targeted feedback, focused just on a single learning goal, makes frequent feedback possible — and prevents really important feedback from getting lost in the noise.

Feedback and lesson plans are inseparable. And we need to think about them that way in order for feedback to be an effective, engaging part of the learning process. For some additional ideas, take a look at another recent blog post on how to provide effective feedback. Or visit our resources page for additional resources on making feedback the focus in the classroom .