Moving Forward with Effective Feedback

Jolene Zywica, PhD

Senior Director of Learning Strategy

Jolene ensures that all of Opportunity Education’s resources, tools, and experiences are designed to effectively support teaching and learning. Jolene earned her PhD in Learning Sciences and Policy from the University Of Pittsburgh in 2013. She’s spent over 18 years designing learning programs and tools that engage K-12 students, as well as adult learners, through active learning and effective use of technology. She’s taken on numerous roles on her mission to help everyone engage in and love learning, including high school teacher, college professor, literacy coach, professional learning specialist, program designer, researcher, and evaluator. Jolene lives in Pittsburgh, PA with her husband and two sons (ages 1.5 and 6).

Summary

As teachers, we all know that students learn more when they’re actively engaged in their learning. While there are many different ways to make learning more active, one strategy we are focused on is establishing effective feedback loops between students and teachers. Effective feedback helps students identify goals, evaluate and synthesize ideas, discuss their work constructively with others, and take actions to improve. We’ve found that teachers who employ these strategies have more engaged and lively classrooms. And, as a result, students develop self-regulation and critical thinking skills and practice a growth mindset.

We have put together the following white paper on effective feedback loops. This paper summarizes the latest research, identifies best practices and provides tools and resources to help teachers engage their students with effective feedback strategies. These strategies are highly effective, and with resources and support from Opportunity Education they can be easy to implement.

Why active learning?

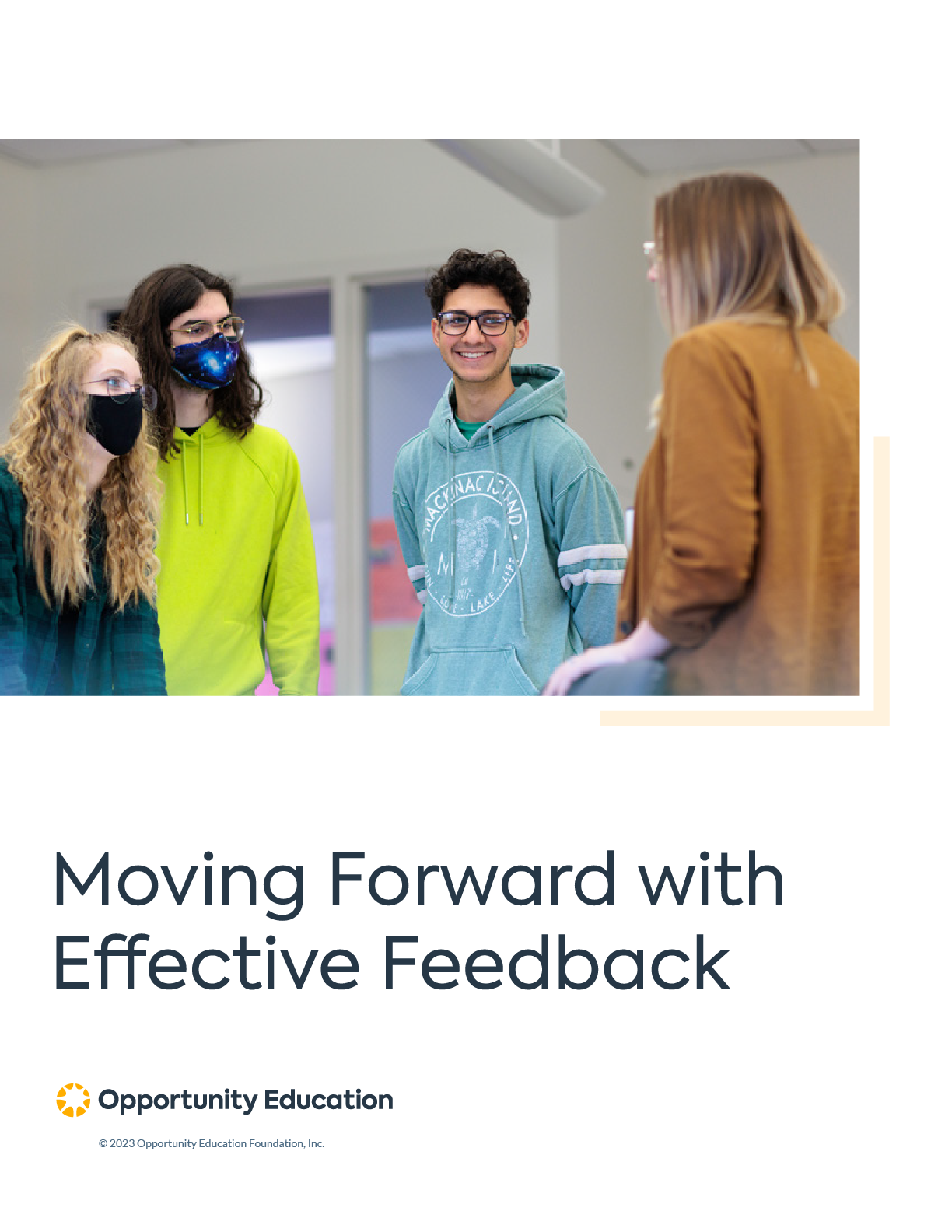

We all learn when we are completely absorbed in what we are doing. Everyone experiences this, whether it is swimming laps in the pool, running, playing video games, cooking, or through some other fulfilling experience. This is often called being “in the zone” or in a state of “flow”.1 The same is true of students in school.

Students learn more when they are actively engaged in their learning and when they “learn by doing”.2,3,4,5 Decades of research on active learning has produced a long list of positive outcomes. These benefits include:

• Increased motivation, interest, and creativity6

• Increased resilience due to stronger peer relationships7

• Improved student attitude and self-esteem

• Improved performance and retention, particularly for students from underrepresented groups8

• Increased level of perceived control in their learning.

Higher education reflects this reality as well. A meta-analysis of 225 studies conducted by Freeman and colleagues (2014) found that college students in traditional lecture courses were 1.5 times more likely to fail than those who participated in courses that employed active learning strategies. They also found such strategies increased student performance on assessments by about half a standard deviation. The results were consistent across subject areas.

These compelling findings suggest that providing support to educators to effectively incorporate active learning strategies should be a priority. Many teachers would like to move away from direct instruction to incorporate more active learning, but they need support and guidance for this way of teaching to be effective and sustainable.

Effective feedback requires active learning

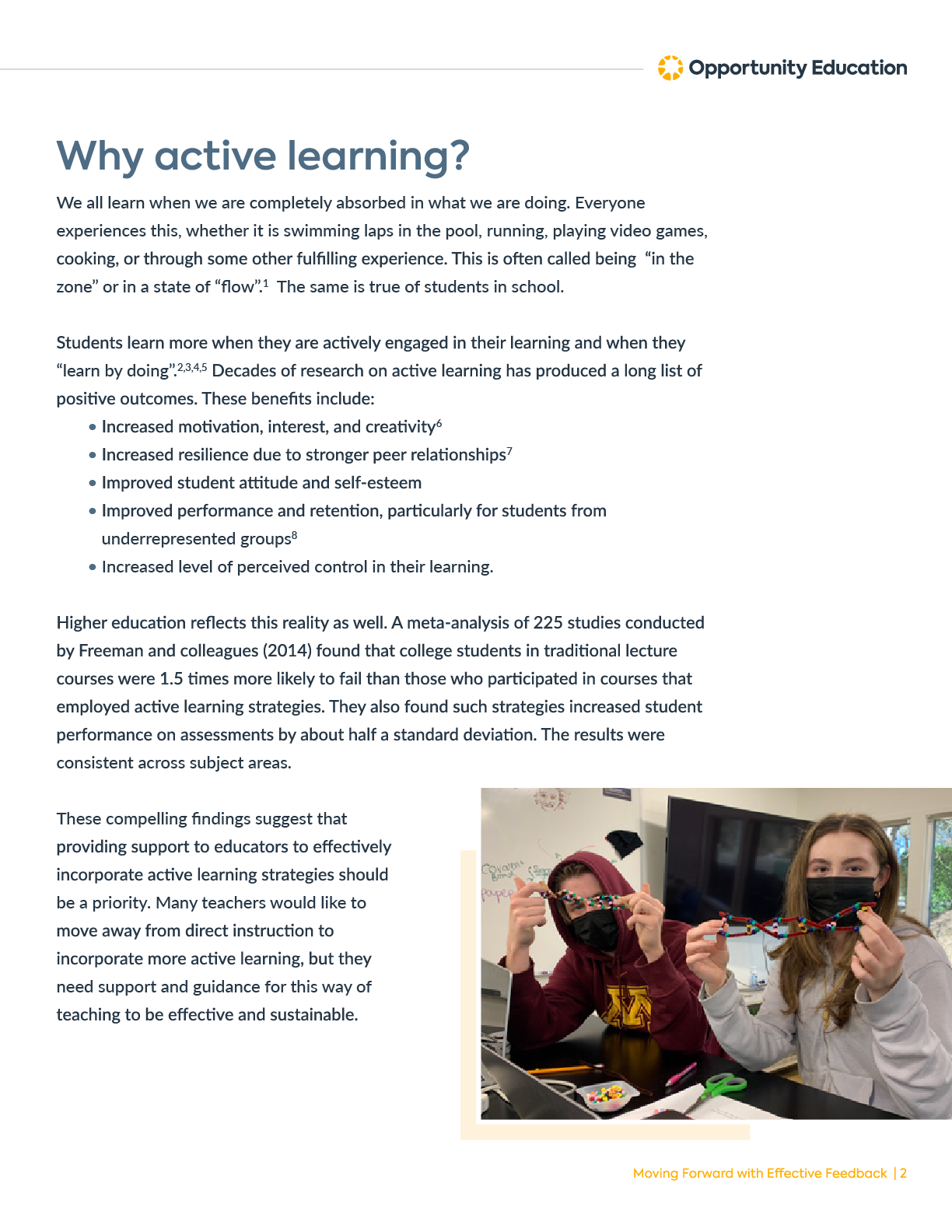

One way to foster student engagement through active learning is by establishing effective feedback loops between students and teachers. Effective feedback requires both teachers and students to actively participate in the feedback process, not just as receivers of feedback and information, but as contributors who work together and each own aspects of the process. The outcomes of this work together is feedback that helps both the student and the teacher move forward – by taking actions to improve skills and practices, work products, instruction, or lesson plans.9

Feedback is much more than the information teachers give students about their work, skills, knowledge, and learning.

Feedback is part of an iterative and responsive process where students can learn and develop skills and mindsets – they reflect, evaluate their work, understanding, and skills, communicate with peers and teachers, and practice a growth mindset. The feedback cycle, when implemented effectively, is an active learning experience in its own right, as students practice and develop skills they will use the rest of their lives.

Feedback and assessment go hand-in-hand

When implemented effectively, feedback can increase student performance.10,11 For low-performing students, feedback can increase achievement as well as students’ motivation to learn.12,13 But, there would be no feedback without first evaluating evidence of student learning and assessing it against goals or standards. Because of this, it is useful to look at the various types of assessment and the feedback each generates.

Assessment of/for/as learning

There are three categories of assessment framed around the purposes of assessment. These include14:

- Assessment of learning

- Assessment for learning, and

- Assessment as learning

Assessment of learning is often referred to as summative assessment. Assessment for learning and assessment as learning are both types of formative assessment. These assessment practices generate evidence of learning and make student thinking visible to teachers, but the ways in which they do that and the type of feedback that emerges is very different.

Want more?

We hope you enjoyed the first part of our white paper. Complete the form below and we’ll email the entire 27 page PDF of our research that contains tools and resources to implement effective feedback in your classroom.

"*" indicates required fields

Citations

1. Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper and Row.

2. Bonwell, C.C. & Eison, J.A. (1991). Active learning: Creating excitement in the classroom. 1991 ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Reports.

3. Freeman, S. et al. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. PNAS, 111(23).

4. Kontra, C., Lyons, D. J., Fischer, S. M., & Beilock, S. L. (2015). Physical experience enhances science learning. Psychological Science, 26(6), 737–749.

5. Prince, M. (2004). Does active learning work? A review of the research. Journal of Engineering Education, 93, 223-231.

6. Owens, D.C., Sadler, T.D., Barlow, A.T., & Smith-Walters, C. (2017). Student motivation from and resistance to active learning rooted in essential science practices. Research in Science Education, 50(1), 253-277.

7. Cassidy, S. (2015). Resilience building in students: The role of academic self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 6.

8. Snyder, J.J., Sloane, J.D., Dunk, R.D.P., & Wiles, J.R. (2016). Peer-led team learning helps minority students succeed. PLOS Biology, 14(3).

9. Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the Black Box: Raising Standards through Classroom Assessment. Phi Delta Kappan, 80, 139-148.

10. Brookhart, S. M. (2008). How to Give Effective Feedback to Your Students. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

11. Hattie, J. A. (2009). Visible Learning a Synthesis of over 800 Meta-Analyses Related to Achievement. New York: Routledge.

12. Boston, C. (2002). The concept of formative assessment. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 8.

13. Ellis, R. (2009). Corrective feedback and teacher development. L2 Journal, 1, 1-18

14. Earl, L. M., & Manitoba School Programs Division. (2006). Rethinking classroom assessment with purpose in mind: Assessment for learning, assessment as learning, assessment of learning. Manitoba